Widely viewed as a positive development, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a 0.1% drop for the Producer Price Index (PPI) in August. Year over year, the PPI grew by 2.6%.

Prices for final demand services declined 0.2%, while the index for final demand goods rose 0.1%.

The S&P 500 reached a record high on the news and the Fed was further encouraged to cut interest rates, which it did to the tune of 25 basis points (0.25%) on Sept. 17.

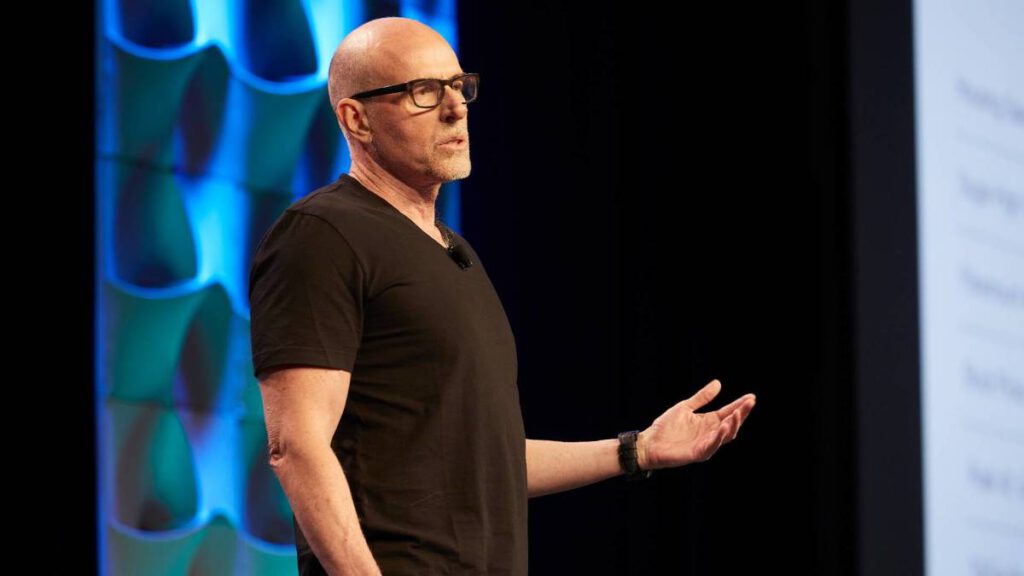

But New York University professor and podcaster Scott Galloway looked deeper into the numbers and found some cause for concern.

Related: Suze Orman warns Americans on 401(k) mistake to avoid

In his Prof G Markets newsletter, delivered to TheStreet by email, Galloway explained his view that the decline is misleading.

“Once you strip out food, energy, and trade services, core PPI rose 0.3% in August, its fourth straight increase. In other words, manufacturers’ costs are still climbing,” he wrote. “The apparent ‘drop’ came from wholesalers and retailers cutting margins, especially in tariff-heavy sectors.”

“Machinery and vehicle margins fell 3.9% in a single month, masking the fact that underlying inflationary pressure remains,” Galloway added. “Meanwhile, CPI (Consumer Price Index) showed consumer prices increasing 0.4% in August, pushing annual inflation to 2.9%. Shelter led the gains, with airfare, cars, and apparel prices also rising.”

Let’s be sure we’re clear on exactly what these indices measure:

- CPI reflects the shifting costs of everyday items and services that households typically purchase — such as groceries, housing, apparel, and fuel. It’s widely used as a key indicator of inflation, showing how the cost of living evolves over time.

- PPI tracks the price fluctuations businesses face when buying raw materials and bulk goods needed for production. While it doesn’t measure consumer inflation directly, it often serves as an early signal: When production costs increase, companies may eventually pass those costs on to consumers, which is later captured in the CPI.

Scott Galloway warns Americans on stagflation

The Fed interest rate cut, as always, is popular with investors as they see a short-term boost in borrowing and spending.

“But that doesn’t mean it makes sense,” Galloway wrote. “Inflation is still running 90 basis points above the Fed’s 2% target. This isn’t a demand problem. Consumers are spending, and stores are full. There are literally lines to get into shops in SoHo.”

“The real issue is supply-side inflation,” Galloway continued. “Tariffs are increasing input costs, forcing businesses to raise their prices or cut margins. Lowering rates won’t fix that. It might put more money in people’s pockets, but that just fuels demand while input prices remain high.”

“Worst-case scenario, we walk right into stagflation.”

Image source: Getty Images

What is stagflation?

Stagflation is a dreaded economic condition marked by stagnant growth, rising unemployment, and high inflation. Unlike a typical recession — where demand drops and prices fall — stagflation combines economic slowdown with surging costs, making it especially hard to fix.

The term blends “stagnation” and “inflation,” coined in the 1960s by British politician Ian Macleod. Economists once believed it unlikely, since inflation and unemployment usually move in opposite directions. Yet history proved otherwise.

More on Scott Galloway:

- Scott Galloway has bold words for Americans on Social Security

- Scott Galloway warns Americans on 401(k), US economy threat

- Scott Galloway’s net worth

In the 1970s, the U.S. faced stagflation triggered by an oil embargo from OPEC, which retaliated against U.S. support for Israel. Oil shortages drove prices up, while growth stalled. The Federal Reserve struggled to contain inflation until Chair Paul Volcker raised interest rates sharply in 1979.

Stagflation often stems from supply shocks — such as war or pandemics — combined with weak growth. Its impact is severe, measured by the misery index, which peaked during Reagan’s early presidency.

It is a tough economic condition to resolve because central banks are forced to choose between fighting inflation or boosting growth.

Behind the Sept. 17 Fed interest rate cut

On Sept. 17, the Federal Reserve shifted from its eight-month stance of cautious observation and implemented a notable 0.25% interest rate reduction. This marked a significant change in its monetary policy approach, signaling a more accommodating tone.

While the decision had been anticipated by many analysts and market participants, the scale of the cut was modest.

Many had hoped for a more aggressive move to counteract weakening labor market conditions.

Looking ahead, nine committee members projected two more rate cuts before year-end, while seven anticipated either one or none in 2025.

This policy shift follows months of pressure from the Trump administration, which has taken steps to influence the Federal Reserve.

These actions have sparked widespread concern among economists and global investors about the central bank’s autonomy.

Related: Suze Orman warns Americans on 401(k) mistake to avoid